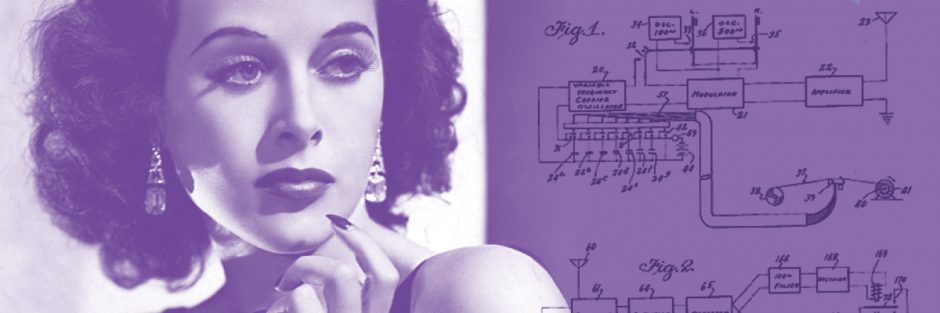

In the 1940s, Hollywood star Hedy Lamarr was known as the most beautiful woman in the world. Quite aside from this, she was also a prolific inventor whose pioneering work helped to revolutionise modern communication.

Hedy Lamarr may have been one of the most beautiful women of her time and one of the most glamorous Hollywood stars of the 1940s – and her face may have been the inspiration for Walt Disney’s Snow White – but she was also a passionate inventor.

One of her early inventions was a compressed cube containing various flavours that was added to water as a kind of effervescent tablet. However, Hedy herself admitted that it “tasted like Alka-Seltzer”.

On behalf of legendary inventor and tycoon Howard Hughes, she occupied herself by working to develop aircraft wings that were intended to exhibit lower drag.

However, her greatest invention was surely a system developed to help the US military defeat German U-boats during the Second World War. Her US patent numbered 2.292.387 describes a radio-control system for torpedoes which was entirely impervious to interference thanks to its automatically changing frequencies.

Nowadays, this concept is a key technology of modern wireless systems such as GPS, Wi-Fi or Bluetooth in the form of a “spread spectrum”.

From trophy wife to weapons technician

Hedy Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, then Austria-Hungary, in 1914. She acted in her first film at just 17, while the 1933 motion picture “Ecstasy” launched her into the spotlight of the film industry – and not just because of its daring nude scenes.

Her first husband, Austrian weapons manufacturer Fritz Mandl, tried in vain to put the brakes on her acting career. Yet life as a “trophy wife” was not to the taste of the budding young actress. In 1937, she fled to London to escape her domineering husband and – as a Jew – also the National Socialist regime before finally emigrating to the USA.

Once there, she was discovered by and contracted to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, making her debut in the 1939 film “Algiers” under her stage name of Hedy Lamarr.

The PR machine at the studio billed her as “the most beautiful woman in the world” – a title she loathed:

During the years she spent in Austria, Lamarr accompanied her first husband to his laboratories and eagerly listened in on his conversations with weapons developers, learning a great deal about anti-ship weapons and control systems in the process.

Using this knowledge, she developed a radio-controlled torpedo which was thus a sure-fire weapon. Nonetheless, she was all too aware that radio signals could be interfered with, meaning that countermeasures to use against a torpedo of this kind would be easy to develop.

She finally found a solution in collaboration with American avantgarde composer George Antheil. For the film “Le Ballet Mécanique”, he had arranged 16 automatic pianos in sequence and synchronised them using punched rolls of paper.

Changing frequency with rolls of paper

Lamarr then came up with the idea of automatically changing the radio -frequency of her torpedo control system using similarly perforated strips of paper.

Working with Antheil, she developed a technical concept which used identical piano rolls – effectively punch cards – in the transmitter and receiver to unpredictably change the signal across a range containing 88 frequencies (the inspiration taken from the automatic pianos is clear to see here: a piano has 88 black and white keys).

The technology seemed too complex to the military, while prejudices against an actress and a composer coming up with such an invention may also have played a part. In any event, the frequency-hopping procedure remained on the shelf for a number of years.

Until the 1950s, to be precise, when the technology was integrated into a new sonar buoy, complete with rotating cylinders for controlling the change in frequency. The technology only really made a full breakthrough once it was released by the military.

Nowadays, the paper strips have been replaced by digital circuits, while the sequences are generated by pseudo-random numbers (PRNs), yet the basic principle is still the same one patented by Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil back then.

The value of inventions based on Lamarr’s original idea is hard to quantify. However, Lamarr and Antheil didn’t benefit in the slightest from their developments. The Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Pioneer Award was first awarded to the pair in 1996 in recognition of their achievement. Lamarr died in the year 2000.

Even though there are surely a great many other inventors and scientists who made greater advances with wireless technologies, Hedy Lamarr remains a role model and a pioneer for that very essence of the spirit of invention: the ability to think outside the box.