Douglas Engelbart’s numerous technological innovations were crucial to the development of personal computing. His work helped make computers operable for everyone.

It was December 1968. An as yet unknown scientist from the Stanford Research Institute stood before a silent crowd in San Francisco and began what would go down in history as “the mother of all demos.” In his 90-minute demonstration, he presented practically everything that would later define modern computer technology: video conferencing, hyperlinks, networked collaboration, digital text processing and something called a “mouse”.

The world of tomorrow

The scientist who demonstrated the potential of collaboration with computers to the astonished audience was Douglas Engelbart. Not a computer specialist, but an engineer and passionate inventor. “Back then, most people thought that computers were only for computation – big brains to crunch numbers. The concept of interactive computing was alien,” he recalled years later. “It was hard for people to grok what we did at my lab, the Augmentation Research Center at SRI in Menlo Park. So I wanted to demonstrate the flexibility a computer could offer: the world of tomorrow.”

Visionary engineer

Engelbart (1925 – 2013) graduated from high school in 1942 and then studied electrical engineering at Oregon State University. During World War II, he served as a radar technician. In 1948, he earned his bachelor’s degree and worked for the NACA Ames Laboratory (a precursor to NASA). He then applied to the graduate program in electrical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, and earned his Ph.D. in 1955. A year later, he left the university to work for the Stanford Research Institute (SRI).

At SRI, Engelbart acquired a dozen patents within two years and worked on magnetic computer components, fundamental phenomena of digital devices and the scalability potential of miniaturisation. In 1962, he published his visionary work “Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework”, in which he outlined his ideas for using computers to enhance human intelligence. Douglas Engelbart once articulated his motivation for his developments as follows: “The complexity of the problems facing mankind is growing faster than our ability to solve them.”

Enhancing human capabilities

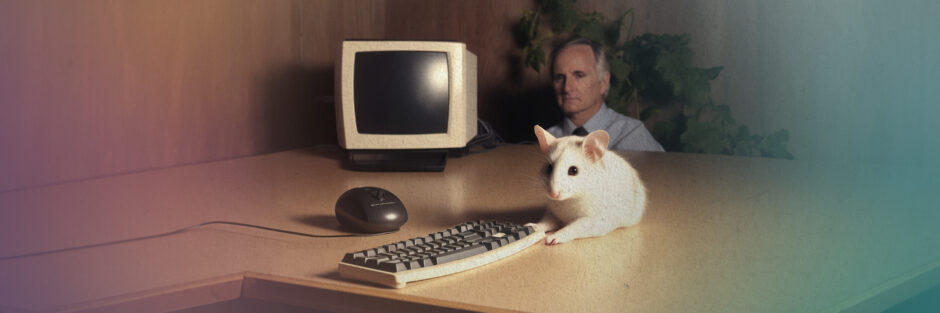

Engelbart wanted to use technological innovations to expand human capabilities. His goal was not for people to have less to do because of technology, but for them to achieve more with it. He saw the computer as a suitable medium to support and enable human intellect, thereby allowing the resolution of highly complex problems more swiftly. An example of this extension of human intellect is the “X-Y Position Indicator for a Display System”, which allowed direct manipulation of elements on the screen. “I first started making notes for the mouse in 1961. At the time, the popular device for pointing on the screen was a light pen, which had come out of the radar program during the war. It was the standard way to navigate, but I didn’t think it was quite right.” Who came up with the term “mouse” for the novel operating device, Douglas Engelbart later could not remember. It just looked somewhat like a mouse: a wooden box with a cable at one end. On top, a red button to click, and below, two wheels that transmitted movement impulses.

Part of a much larger project

“The mouse was just a tiny part of a much larger project that aimed to improve human intellect,” Engelbart said. Because this rudimentary-looking device greatly facilitated the operation of a graphical user interface – also a development by Douglas Engelbart and his team. A graphical user interface (GUI) uses visual elements such as windows, buttons and menus through which the user can interact with the software. Initially, computers consisted only of text blocks and required extensive knowledge of programming and computer interfaces to operate them.

Foundation for Apple’s success

However, Engelbart was perhaps too far ahead of his time; the presentation at the Fall Joint Computer Conference and the significance of his inventions were quickly forgotten. Engelbart failed to convince SRI, investors or other potential sponsors of his vision. It wasn’t until 1980 that he signed a licensing agreement with the two Apple founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak for the patent of the mouse – receiving 40,000 US dollars for it. Four years later, Apple introduced the “Macintosh” based on Engelbart’s ideas: with a mouse and graphical user interface. Today, Engelbart’s vision of a computer for everyone has long since become a reality. When he died in 2013, Apple co-founder Wozniak honoured him with the words: “Everything we have in computers can be traced to his thinking. To me, he is a god. He gets recognised for the mouse, but he really did an awful lot of incredible stuff for computer interfaces and networking.”